Baby green herons and phenology

“There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night and spring after winter.”

~ Rachel Carson

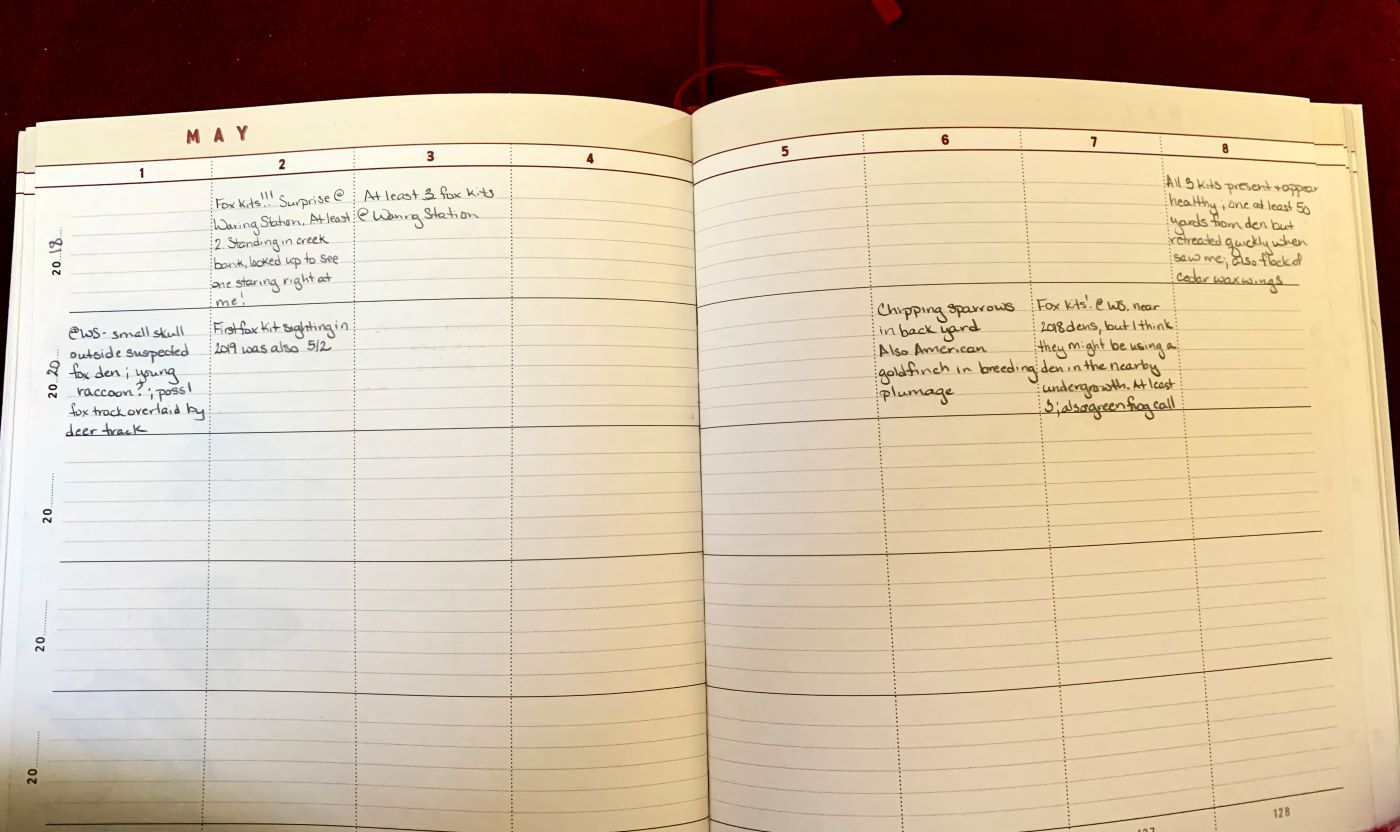

Phenology is the study of the timing of biological events, particularly with regard to climate, plants, and animals. It can be (and is) studied scientifically, but all good naturalists should have their finger on the phenology of events near their home. I try to make note of things like the first and last snow of the winter, appearance or disappearance of migratory animals, such as the barn swallows that nest in the dam on my local lake, and when the forsythia begins to bloom each spring. I keep track in a phenology calendar. I traveled so much in 2019 that I didn’t keep good records for that year, but I have good notes on 2018 and 2020 thus far, and I did record some sporadic observations in 2019, too.

One very reliable phenological indicator near my home is the migration and nesting of green herons. Green herons are squatty little birds compared to most herons…small, stocky and compact. They live and nest near the water and prey on small fish and other aquatic creatures, such as crayfish and crabs. They’re wicked clever, too, and have been observed using tools, such as wiggling twigs in the water to attract fish. The eastern half of the United States is breeding territory for them in the spring and summer. They spend their winters in Florida, Cuba, and central and South America. I always make note of the first green heron I see in the spring. I don’t usually mention them in my notes throughout the summer except to document their nesting behaviors because they’re common and I see them nearly every day. I start to note spottings again in September because you never know when you’ve seen the last green heron of the year until after the fact. Learn more about phenology here.

I have been able to photograph green heron babies at this lake every year since 2016. This is the youngest I’ve ever been able to capture them because usually the nest is too obstructed, and I can’t get a clear shot of them until they fledge. I watched this nest being built, made note of when mama started incubating eggs, and now I’m waiting to document the date the babies fledge! There are four of them, and they’ve only just begun to branch (step outside the nest onto nearby branches.) They should be fully feathered but still sporting little fluffs of down, especially on top of their heads, in time to leave the nest when they’re a month old.

(Looking up hopefully at mom…or dad. The males and females look alike, and they both feed the nestlings.)

Sometimes green herons raise two broods per year, so I might get a chance at another batch of babies later this summer, but I might not. Regardless, they are a joy to watch, and as reliable and common as they are, it will never stop making my heart leap when the first one appears each spring.